TRANSCRIPT

Bernadette Angus lives in the remote Western Australian community of Ardyaloon on the Dampier Peninsula, more than two and a half thousand kilometres from Perth.

The first thing she does when she wakes up in the morning isn’t check her phone, or the weather.

"Hello; this is our typical house, in Ardyaloon."

It's the small digital screen fixed to her wall: her electricity meter.

When the number on the meter hits zero, the lights go dark.

That's because here, and in many remote Indigenous communities across northern Australia, households don’t receive electricity bills.

Instead, they prepay for power, topping up credit much like a mobile phone - and when the money runs out, the power cuts off almost instantly.

"All depends like if you've got a job, if you are on the dole, or if you just have to live from week to week... Because $20 it will only last maybe one day. All depends on what you got. You got a deep freezer, you got a fridge, and air conditioning. But when my kids come I would have all three going."

A day’s worth of power can cost twenty to forty dollars, sometimes even more during the summer heat.

Bernadette says she’s constantly rationing her usage, especially when her three kids are home.

Back on the road, about twenty-seven kilometres south, in the neighbouring Indigenous community of Djarindjin,

"I go to the shop and buy $20 power"

Audrey Shadforth has a similar story.

Audrey says her power ran out just the night before we interviewed her.

"We had power all night then about 9pm it go off. By 8.40 we have to hurry look for power, look for some money to pay for power. That only gave me like what, few minutes."

Across Australia, around fifteen thousand First Nations households use prepaid electricity.

For most, it’s not a choice; it’s the only option their retailer offers.

A report by Original Power, together with Notre Dame’s Nulungu Research Institute and Western Sydney University, reveals just how widespread the issue is.

It found some sixty-five thousand First Nations people live under mandatory prepayment systems — with homes disconnected on average more than thirty times a year.

Lloyd Pigram is from the Broome Nulungu Research Institute.

He's one of the researchers who conducted interviews in remote communities to help deliver the report, called The Right to Power.

"Old people with chronic illnesses running out of power as we were doing the survey, to people actually needing top up as we were doing the interviews... It's hard not to get emotional or angry because it is like the power's off and they've actually got not long left to live. They are struggling to you know, they know the power on."

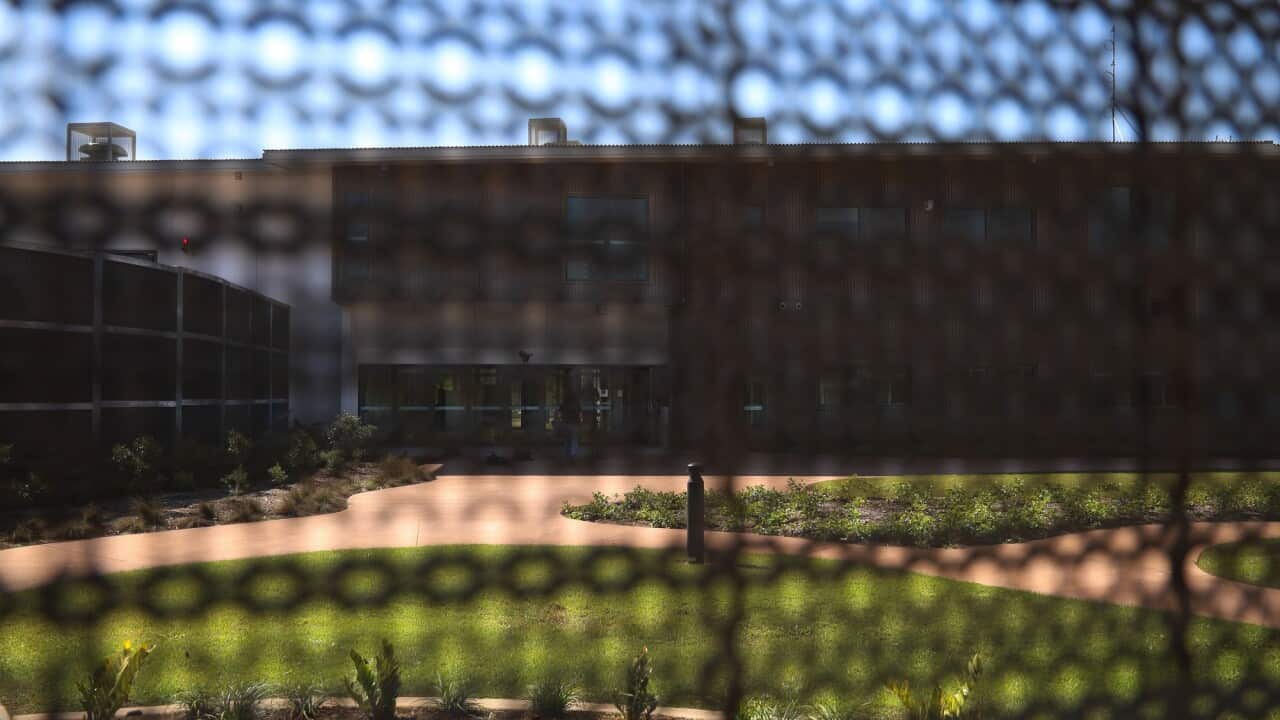

The reason for this is that in remote parts of Australia, many communities were never connected to the main power grid and relied on small local systems, which made billing and payments hard to manage.

So power companies introduced prepaid meters, ensuring bills were covered upfront, but also creating a system where regulators have focused more on collecting payments than protecting people’s right to power.

Dr Josie Douglas from the Central Land Council says without stronger consumer protections, communities will continue to fall behind national Closing the Gap targets.

"Out of the four jurisdictions, the Northern Territory fairs the worst. This is outrageous. Aboriginal people in remote communities are experiencing 59 disconnections per year. We know the disconnections have a very strong correlation with heat. When the temperature rises, disconnections increase."

The report warns that with extreme heat becoming more frequent, the consequences of power loss can be deadly.

The CEO of Energy Consumers Australia Brendan French says that no electricity means no refrigeration for food or medication, no cooling, and no access to safety alerts during heatwaves or cyclones.

"There are tens of thousands of households living without the consumer protections that you and I enjoy. And also none of the opportunities as an irony, that in centre of Australia a hundred days over 35 degrees, people can't get access to solar power to reduce their bills. The brilliance of this report though, is that it doesn't just focus on history or injustice and equality. It focuses on the roadmap."

In a statement, Climate and Energy Minister Chris Bowen said the government has received the report and appreciates the information about energy security in remote communities — but has stopped short of any firm commitment, saying energy delivery remains the responsibility of states and territories.

A Western Australian government spokesperson said it will consider the report’s recommendations, highlighting Horizon Power’s rollout of advanced metering and solar programs to improve reliability and energy equity in remote communities.

The Northern Territory government also says it would also review the report and consider any recommendations to improve coordination or simplify access to relief programs, while Horizon Power added that it provides hardship support and energy coaching, but that wider policy decisions rest with government.

With extreme weather events like heatwaves predicted to become more frequent, keeping the power on has never been more important.

Back in Ardyaloon, Bernadette Angus says her community has learned to look after one another.

"That's what all families do, they help each other out. Even today someone caught the turtle and we all went there, bring us up, to come over for a feed. So nobody starves."